In IL2 Sturmovik engine damage is modeled very well. It is modeled so well that understanding how to manage your engine once damaged is worth your time. A generic damage assessment would consist of validating your control surfaces and the state of your engine. This doc is primarily written for IL2 but can be used for other Sims as well.

BF 109 Engine Management for BFT

For Basic Flight Training we have you run at emergency power settings in the BF 109 F4. Ensure you have mapped your manual prop pitch control key. Optionally, also map manual radiator control if you wish to manage that during your emergency procedures.

The general BF 109 F4 emergency settings are as follows:

- Try to maintain at least 220 kph

- Keep around 1,500 RPM

- Set your manifold to 0.8 ATA

- Coarsen your prop pitch to 8:30 (prop pitch "clock" gauge)

Damage Assessment

Control Surface Assessment

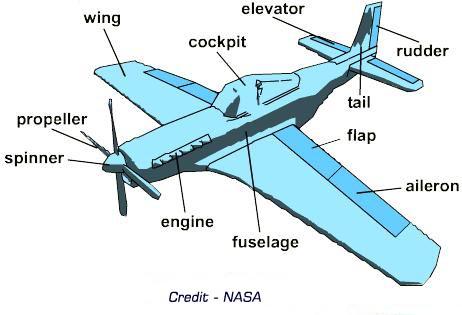

In the event of suspected plane or engine damage it is wise to take a quick assessment of what is indeed damaged and be aware of what the impact may be. First, you need to understand the different parts of your plane and what they do.

A quick overview of control surfaces:

- Ailerons - Controls ability to Roll, can make turning more difficult if damaged.

- Elevators - Controls pitch, can make climbing and diving more difficult if damaged.

- Rudder - Controls yaw, can make turning and crabbing on the horizontal plane more difficult.

- Flaps - Allows you to produce more lift at lower speed, makes landing harder or slow turn fights harder when damaged.

If you couldn't already tell loss of rudder or flaps is not as serious as loss of elevator or ailerons. Its ultimately a judgment call on the part of the pilot at the time but you may be able to continue combat if damage to the flaps or rudder occurs. You almost certainly want to disengage if you suffer damage to aileron or elevator.

Most damage assessments can be done by quickly glancing at these fundamental parts of the plane. You just need to glance out over both wings and back at your tail. Note, sometimes your flaps are on the underside of your wing and you can't see them. Rudder may also not be visible requiring you to asses it via control input.

To test via control input (assuming you are not in combat). Quickly attempt to roll left/right, pitch up/down, and yaw left/right. Note any sluggishness in response to input as possible damage. Note that even if you have lost control of your elevator or aileron that might not mean you have lost the ability to trim your aileron or elevator. In the event of a loss of elevator or aileron try to use trim. You also may be able to manage the journey home with a loss of say your ailerons by navigation with solely your rudder and elevators. Note, you ever want to try this... dive with a Yak past it's max dive speed.

If after an assessment you don't feel confident you can maintain control of your craft attempt to ditch or belly land depending on your altitude.

Engine Assessment

To asses your engine you want to take note of what is going on outside as well as inside your plane. In short, check if you are venting any gas or smoke and what your control panel gauges can tell you. Condensation trails (con-trails) occur at high altitudes and do not denote engine damage.

If you find you are venting (not con-trailing), asses what color is it:

- Venting black smoke - possible oil line or catastrophic engine damage

- Venting light greenish smoke - possibly fuel leak.

- Venting white smoke - possible coolant leak.

Black smoke is very bad, or not. It's hard to tell, either way you want to plan to disengage and head home. Green vapor is probably the least threatening. It just means you are leaking fuel and you can monitor this via your fuel gauge. You may even still fight with a fuel leak. White vapor on the other hand is bad, it means a coolant leak which tells you engine failure is eminent. Once you are out of coolant your engine will seize and you don't have a reliable way in most planes to determine when this will occur.

Check your gauges, if you see RPM or water temps "wobbling" or the engine is revving that is a bad sign. This probably means you don't have long until total engine failure. If gauges are steady then direct your focus to Manifold Pressure, RPM, Prop Pitch, and temps.

Emergency Procedures

Dead Stick

At this point you have assessed possible damages and have some decisions to make. If you engine is dead or prop is trashed, you are dead stick. If dead stick, close your radiators and raise flaps/gear and go into a shallow dive. You have to give up altitude for just enough enough speed to stay in the air. Watch your airspeed combined with your dive rate. Now is the time when knowing your planes stall limits is important. Try to make your way to the nearest friendly airfield... or friendly territory. If you are taking fire either ditch or take evasive action leading to an immediate belly landing.

The method of (crash) landing is ultimately your judgment call given the specific situation you find yourself in. However, there is a strong argument to be made about not deploying landing gear when dead stick. Landing gear creates a lot of drag and with no forward thrust your speed could quickly drop below your stalling point. You also may be loosing altitude too fast for a proper wheel landing which could cause you to bounce and/or tip over during landing. Keep you nose up during a belly landing and try to land flat, deploy your flaps when close to the ground.

Damaged Engine Management

If your engine is functional but you are venting smoke or fluid, disengage from combat as soon as safely possible. Because we are imaginary pilots, some like to hang in until the end and go out in a blaze of glory... every time. If that is you, more power to you. If however you want to save that blaze of glory for a particularly opportune moment later on, or more importantly... deny the enemy a kill, read on.

Assuming you are just venting fuel, go for gradual altitude if not being pursued. Keep an eye on your fuel gauge. You want to gain enough altitude so that if and when you run out of fuel you can glide to safety and possibly land. For landing dead stick, read above. Most of the time you should be able to find your way home and land normally, unless of course it is a heavy/multiple fuel leak or you where flying on fumes. Don't be afraid to push your engine as hard as you can.

If you are venting coolant or oil (black smoke) many of the same rules apply as for fuel leaks. Go for altitude, open your radiators. Set your fuel mixture to rich if applicable and try to maintain coarse prop pitch, low RPM, low Manifold pressure, and low temps. You are in triage mode now, one of these may have to give. With oil and coolant leaks it's only a matter of time until engine failure and you have very little indication when this will occur. You can attempt to juggle engine setting with radiators and altitude. Some like to push the engine in a climb and then coast in a dive and give it time to cool. The choice is yours. We encourage you to set constant low power engine settings and maintain a steady course.

A note about bombers and twin engine planes. In a bomber such as the HE 111 you are heavy, very heavy. You will drop, fast. Plan on not making it very far if you are dead stick. Same rules apply otherwise. Just remember that you can use your trim also to keep your nose up, plan on a belly landing in the nearest open space. If you only loose one engine remember to use yaw input to help compensate for the loss of your engine.

In general, you want to maintain 1,000 - 1,500 RPM with a coarse prop pitch and low manifold pressure. Use your judgment based on the above to try and maintain a speed above your stall point while at the same time avoiding blowing out your engine.